Following the release of Peggy Day’s 1988 monograph, An Adversary in Heaven: Satan in the Hebrew Bible, scholarship has largely accepted that the portrayal of “Satan” in the Hebrew Bible is fairly different from his portrayal in later Jewish and especially Christian literature. The book of Job has often been cited as an example of just how different the ancient Hebrew understanding of “the Satan” is from the authors of the New Testament’s. However, the present study seeks to undermine this notion and prove, contrary to Day, that Job’s Satan is much more reminiscent of Christianity’s villain than many scholars have been led to believe. It will be argued that the chief inspiration for Job’s Satan is the character of the Serpent from Genesis 1-3, and this association is carried throughout the dialogues, and culminates in God’s discourse on the Leviathan in Job 41.

Job’s Literary Unity

Before looking into any of Day’s specific arguments concerning the Satan in the book of Job, it is first necessary to unpack the lens with which she approaches our text. Day begins by rightly affirming that, contrary to the view of some, the book of Job does indeed have “basic structural integrity,”1 despite the many stylistic changes that one encounters throughout the narrative. Although it certainly can be argued, on the basis of these stylistic discrepancies, that Job is composed of several (perhaps originally independent) sources, and may even be the work of several authors over a long period of time, its essential literary unity was defended at the time of Day’s writing,2 as it is today. Indeed, C.L. Seow has noted how Job’s idiosyncratic combination of several different genres into one has parallels in Ancient Near Eastern literature, meaning that these “differences, then, do not necessarily suggest diverse authorship but may rather point to a single composer utilizing different genres and styles.”3 Regardless, Day is correct that “it is more [exegetically] profitable to posit a basic integrity to the book of Job, and try to make sense of the component parts in light of the overall composition.”4 It is with this assumption of basic literary unity that we will continue our investigation of Job’s Satan.

Job’s Usage of Irony

Where the present study will disagree with Day is in her treatment of irony in the book of Job. Certainly, it cannot be doubted that this literary device is on full display throughout the book. For example, Day correctly cites Job’s lament in 3:23, “Why is light given to a man whose way is hidden, whom God has hedged in?,” as an ironic callback to the Satan’s remark in 1:10, “Have you [God] not put a hedge around him [Job] and his house and all that he has?” Little does Job know that it is precisely because God has put a “hedge” of protection around Job that He allowed him to endure these sufferings! Virginia Ingram enlists several more examples of irony in Job,5 such as Job’s quip in 26:2-3 where he curses his adversary by ironically “praising” him, and Eliphaz’s ironic “encouragement” of Job to seek God’s justice in 5:1-21, among others. Thus, the fact that irony is present (and abundantly so) in Job is not denied. Instead, it is what Day extrapolates from this irony that the present study finds problematic.

According to Day, there are instances in our text where the character of Job will say something that he believes to be true, but ironically, it is not. This belief is absolutely central to her argument that Job misidentifies the Satan as his heavenly advocate (16:19-21) and redeemer (19:25-27).6 In order to defend this thesis, Day argues that the prologue at the beginning of Job sets up the entire book to play out with a “gap between the knowledge of the audience and that of the performers [in the story] that paves the way for irony.”7 As mentioned, Day’s favorite example of this is the ironic connection between 1:10 and 3:23, of which she writes, “Job is not aware of the irony in his statement, but the audience, privy to a competing view of reality [from the prologue], could not help but see, in my estimation, the irony of Job’s statement.”8

However, what Day fails to consider is the fact that, while Job indeed does not understand the irony of his lament, the irony is precisely that Job does not understand just how correct he is. That Job “perceives [the Lord’s] hedge as the cause of his sufferings”9 is actually a correct perception. The knowledge that the audience gleans from the prologue, which Job himself does not, is that it is precisely because of God’s special care for His servant Job that these trials have befallen him. Remember, it was the Lord who pointed out Job to the Satan, not the other way around (1:8, 2:3). If it were not for the Lord thinking so highly of “my servant Job,” the Satan would have had no reason to even notice him. Below it will further be argued that the imagery of 41:2, wherein the Lord leads the Leviathan around with a hook in his nose, is employed to underscore this very fact that it was the Lord guiding the Satan’s assault on Job every step of the way.

Thus, while Job indeed betrays ignorance of his situation through irony, he does so in a way that is factually correct within the narrative. This makes sense of the Lord’s statement to Eliphaz in the epilogue that, “My anger burns against you and against your two friends, for you have not spoken of me what is right, as my servant Job has” (42:7). Unlike his three friends, the narrative informs us that Job spoke correctly about the Lord, even if he did not always realize the full extent of his correctness. As such, the fact remains that the only examples (other than those she is trying to prove, which we will examine below) Day puts forward of irony reflecting an incorrect perception of reality are from those whom the text condemns as speaking falsely,10 which should cast significant prima facie doubt on her identification of the Satan.

The Identity of Job’s Advocate

Let us now consider the actual Joban texts that Day uses to build her thesis that the Satan is to be identified as the heavenly advocate and redeemer. I have decided to group together the first two texts, 9:33 and 16:19-21, because, as it will be shown, her arguments for each one create an irreconcilable contradiction that ultimately undermines her case.

To begin, the second of the texts Day appeals to in support of her thesis is 16:19, “Even now, behold, my witness is in heaven, and he who testifies for me is on high.” Commenting on this text Day writes, “Job believes that right now… there exists a heavenly advocate who could bring his case before God.”11 Building on her prior attempt to demonstrate that characters in Job repeatedly use irony to highlight information that only the audience knows from the prologue, Day interprets Job’s advocate as a reference to the heavenly Satan. Job thinks he has an advocate with God in heaven but, ironically, he actually has an adversary. However, as we argued above, the way the character of Job uses irony in our text is different from the way that his friends do. As the epilogue informs us, Job is correct in everything he says, while his friends are incorrect. Thus, the text demands a different explanation.

Indeed, it appears that Day’s thesis itself requires us to seek an alternative interpretation as well. To see why, consider the first text that Day uses to support her thesis, “There is no arbiter between us [Job and the Lord], who might lay his hand on us both” (9:33). According to Day, Job “longs for a being who could take both himself and God to task within the context of a trial.”12 She invokes this as yet another example of factually incorrect irony on behalf of Job. While Job longs for a heavenly moderator, from his perspective, “such a being does not exist.”13 In reality, however, “Not only does such a being exist, he’s the one who has gotten Job into his present fix,”14 i.e. the Satan. The problem with this interpretation of 9:33, however, is that it blatantly contradicts what Day said about Job’s statement in 16:19.

As Day herself points out, the “arbiter” of the former text clearly cannot be the same being as the “advocate” in the latter text, for, “how then could the [advocate] whom Job calls upon be the same character as the one he pronounced nonexistent?”15 In other words, if, as Day concedes, Job does not believe there to be any mediator whatsoever between him and God, then Day’s assertion that Job believed that “there exists a heavenly advocate who could bring his case before God,”16 must be false. If, in Job’s mind, the only parties at his trial are himself, God, and the accusers, yet there is also an advocate thrown into the mix, then, as John Hartley argues, “the best candidate for [Job’s] defender that can be found [in 16:19] is God himself.”17

Now, Day does address this “traditional” interpretation of 16:19, wherein the advocate is somehow the Lord Himself, however she dismisses it rather quickly. Providing her own translation of 16:21, she posits that since the heavenly advocate “argues on behalf of a man with God,”18 it is “impossible” that Job intends to identify the advocate with God.19 Why exactly this would be impossible for an antique author steeped in the Hebrew tradition is left unexplained, as Day simply asserts this to be the case without evidence. However, this blind assertion is rather odd given Job’s traditional placement in the genre of “wisdom literature,” which is not a stranger to apparent speak of plurality within God. For example, the book of Proverbs is well known for its personification of “Lady Wisdom” as a kind of divine being who was pre-existent with God in the beginning (Prov 8:22-31).

Moreover, the Hebrew Bible itself contains much material that would lend itself to the existence of divine plurality.20 In Genesis 1:26-27, for example, we are told, “Then God said, ‘Let us make man in our image, after our likeness…’ So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them.” Although some have interpreted the “let us” in this text as a reference to the divine council, Christopher Kou has recently demonstrated why this cannot be the case.21 If mankind was made “in his own image… in the image of God” per v. 27, then the “us” and “our” of v. 26 must have God as their subject. In other words, “the image of God” must be identical to “our image,” meaning that the plurality is truly being predicated of God Himself, and not any other beings.

Indeed, this even sheds light on how mankind exists as the image of God according to the author of Genesis. As Kou explains: “God [in Gen 1:26-27] addresses God (not gods) and then acts—unilaterally, in concert—to create an image who, analogous to himself, has plurality in unity.”22 Mankind was created as a plurality in unity, one divine image in male and female; this is clear from v. 26, “in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them.” If an image is supposed to bear resemblance to its prototype, then it is only natural to conclude that Genesis 1 portrays God as a being who also exists in both unity and plurality. This is incredibly significant to our present study of Job because, as it will be shown below, the book of Job draws extensively from the opening chapters of Genesis for its overall theological message, and so a reference to plurality within God Himself makes perfect sense.

Thus, given the facts that (1) the character of Job is never factually incorrect in his usage of irony, (2) Job explicitly denies the existence of a mediator between himself and God, while also affirming that he has an “advocate” who is “on high,”23 and (3) the tradition in which the book of Job was written allows for the existence of plurality within God, we must conclude that Day is incorrect to identify the heavenly advocate as the Satan. As such, since Day herself states that the third text she wields in favor of her thesis, 19:25-27, depends entirely on her interpretation of 9:33 and 16:19-21 being correct,24 the present study will simply dismiss her understanding of this text as irrelevant. However, we will come back to this text below as we work through our own interpretation of the characters of the Lord and the Satan within Job, and it will be shown to present a deathblow to Day’s perspective.

The Satan and the Serpent

With Day’s identification of the Satan as the heavenly advocate now thrown out, the present study seeks to propose an alternative understanding of the Satan within the Joban narrative. As suggested above, we maintain that the proper context for understanding the book of Job’s portrait of the Satan is the book of Genesis.

We see the first nod to Genesis in 1:1 where our main character is described as תָּ֧ם, an adjective that, elsewhere in the Hebrew Bible, only refers to a named individual in Genesis 25:27.25 More explicit, however, is the fact that the entirety of Job’s prologue reads like a copy of the scene from Genesis 1-3. Just as the garden of Eden was a secure place, located in the east (Gen 2:8), and likely enclosed,26 so does the book of Job’s Satan note how God had “put a hedge” of safety around Job’s land (1:10), which was also in the east (1:3). Seeing this safe environment, the Satan, like the Serpent (Gen 3:1-2), wanted to go in to stir the waters (1:11-12), and, after this happened, both Adam and Job were put to the test by their wives. Job, however, did not listen to the voice of his wife (2:9-10) as Adam did (Gen 3:6, 17), teasing that Job’s story may end differently than Adam’s. At the very least, by humbly pronouncing over himself, “Naked I came from my mother's womb, and naked shall I return” (1:21), Job avoided hearing the condemnatory words that God pronounced over Adam, “you are dust, and to dust you shall return” (Gen 3:19).

This parallel between Job and Adam then continues with the book’s characterization of Job as a king. We can see Job’s royalty shine through his great number of possessions, including “very many servants” (1:3), the regular feasts his children enjoy, and his abundant access to sacrificial animals (1:4-5). Indeed, Job being the greatest “of all the sons of the east” (1:3, מִכָּל־ בְּנֵי־ קֶֽדֶם) is linguistically reminiscent of King Solomon having wisdom that surpassed the wisdom “of all the sons of the east” (1 Kg 4:30, כָּל־ בְּנֵי־ קֶ֑דֶם). Like Solomon, Job is depicted as the greatest eastern king. This royalty is also prominently featured in the Satan’s direct attacks against Job, which all center around destroying his kingdom. The Satan has all of Job’s heirs killed (1:19), his animals and servants taken away by rival nations (1:14-17), and finally Job’s “three friends” decide to “make an appointment” with him. The verb used to describe what Job’s friends do throughout the narrative is יָעַד, which can refer to a simple meeting (Ex 25:22, 29:42, 1 Kg 8:5), however it can also refer to a conspiracy. Significantly, two places in the Hebrew Bible where this word does refer to a conspiracy, Numbers 16:11 and Nehemiah 6:2, 10, are also in the context of three individuals gathering together against the Lord’s servants.27 Thus, it is very likely that Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar were attempting to overthrow Job’s rule.

Job’s royalty ties him to Genesis’ first patriarch because, like Job, Adam also exercised royal dominion over an eastern land (Gen 1:28).28 Adam’s royalty is most prominently seen in his reign over the animal kingdom (Gen 1:26 cf. 2:19-20), which fits nicely with Job’s royal status being seen through his sovereignty over 11,000 animals in the prologue (1:3) and then 22,000 in the epilogue (42:12). It is worth highlighting that twenty two is the number of letters in the Hebrew alphabet, and so Job’s final animal count containing this number suggests that he, like Adam, was given dominion over everything from א to ת.29 Indeed, another royal figure associated with the animals in the Hebrew Bible is, once again, King Solomon. After praying for the knowledge to “discern between good and evil” (1 Kg 3:9),30 Solomon received wisdom that enabled him to teach the nations about the animal kingdom (1 Kg 4:33-34). As we will explore in more detail below, the reception of wisdom about animals will also play an important role in King Job’s story (39:1-30), a story that ends exactly the opposite of Solomon’s,31 which further ties these characters together.

All of this to say, if the book of Job’s prologue was written with the story of Genesis 1-3 in mind, then it must be conceded that, just as Job fulfills the role of Adam, so does the Satan fulfill the role of the Serpent who fell under God’s curse in Genesis 3:14-15. In other words, right from the beginning, the author of Job intentionally portrays the Satan as the primordial enemy of mankind of whom it was prophesied that the seed of the woman would crush his head.

God Answers Job

If there was any doubt that the figures of Job and the Satan are intentionally paralleled with Adam and the Serpent from Genesis 1-3, the epilogue of Job should put that to rest. However, it is first important to place these final speeches of God in their proper context. Above we analyzed two of the Joban texts in which scholarship has “detected a third party mediating between Job and God,”32 namely 9:33 and 16:19-21, among which there is a third that we have not yet exegeted, 19:25-27. It is our position that the latter two of these texts exhibit Job’s tendency throughout the dialogues to demand “a hearing before the Supreme Court” of heaven,33 which is precisely what he gets in chapters 38-42.

This desire of Job’s is laid out explicitly in 13:3, “But I would speak to the Almighty, and I desire to argue my case with God.” Given we have already laid the groundwork for an identification between 16:19’s advocate and the Lord, we can understand this passage as yet another instance of Job seeking a personal audience with the God of heaven. We are clued into this by 16:21’s usage of the word יָכַח to describe one who “argues with God,” the same term used by 13:3. Job desires to be judged by God because He is his only “advocate,” which we as the readers already know from the prologue. The only character who has consistently affirmed Job’s innocence throughout the narrative is God (1:8, 2:3); everyone else, including the Satan and Job’s “friends,” has attempted to undermine this very verdict. Since he is aware of his own innocence, Job knows that, if only he could get his case heard, the God of truth would decare him to be in the right, which He later does (42:7-8).

This is made more explicit by 19:25-27, which, as Day herself affirms, has the same mediatorial subject as 16:19-21. Hartley makes a very compelling argument that Job’s “redeemer” is none other than the Lord. He points out that, in Israel’s theological tradition, the title of “my redeemer” (גֹּ֣אֲלִי) has a long association with the nation’s God: “It is rooted in the interpretation of Israel’s deliverance from Egyptian bondage (e.g., Exod. 6:6; 15:13; Ps. 74:2; 77:16 [Eng. 15]). The theology of this title is that since the Lord brought Israel into existence as a nation, he recognizes his obligation to deliver them from all hostile foes.”34 Hartley further highlights the significance of the “redeemer” being the one who “lives” (חָ֑י), a word that Job uses in 27:2 to refer to “God” as the one who “lives.” He writes, “Job is saying that his redeemer is alive, able to come to his aid. Even should he die, his redeemer will survive him and be able to restore his honor.”35 This explains Job’s statement that, “at the last he will stand upon the earth” (19:25). Job is fully confident that he will get his personal audience with the Lord, and when he does, he will be declared righteous.

This theme is what builds the foundation for the book’s epilogue, wherein Job’s redeemer finally does stand upon the earth to vindicate His servant. The preceding speeches of Elihu make this clear. Elihu affirms his allegiance with Job’s wicked friends by agreeing with their overall argument that Job is guilty (33:12). He then explains that, unfortunately for Job, God does not waste His time speaking directly to men. The Lord may speak in “a dream” or “a vision” (33:15), He might sends trials (33:19-20) or an angel (33:23), but He will never speak to Job directly. As Seow writes, “Job wants God to answer him (31:35), but Elihu will answer Job instead, because God is too great for any mortal and does not answer a legal challenge by anyone (33:12–13).”36 Elihu insists that he is the answer from God (35:4), because God Himself is under absolutely no obligation to give answers to mere men (35:9-15). As Toby Sumpter describes Elihu’s point of view, “The fact that [God] does not answer does not impugn his justice, it only confirms Job’s ignorance (35:14-16).”37

Indeed, in his final speeches, Elihu describes God as an unfathomable storm. “Behold, God is great, and we know him not” (36:26), says Elihu; we cannot “understand the spreading of the clouds” or “the thunderings of his pavilion” (36:29). The “thunder” that comes “rumbling” out of the Lord’s voice performs mighty deeds that we simply “cannot comprehend” (37:2, 5). Can we speak to the divine storm? “We cannot draw up our case because of darkness” (37:19), answers Elihu. “The Almighty—we cannot find him” (37:23). In Sumpter’s words, “Because God is such a great and terrible storm, Elihu tells Job to stop expecting God to speak with him. Instead, Job needs to submit to the storm and repent of his sin. That is all anyone can do.”38 However, in a single statement, the mouths of all of Job’s adversaries are shut: “Then the Lord answered Job out of the whirlwind” (38:1). Unlike what Elihu claimed, the storm does speak back. Job’s redeemer and advocate would indeed stand upon the earth to hear His servant’s case.

The Satan, the Serpent, and Leviathan

With the context of the Lord’s speeches now established, it should be clear that, contrary to popular belief, the Lord’s answer to Job is just that, an answer. Job’s adversaries have consistently said that the Lord does not answer to mere men, and that Job was in the wrong for demanding an audience with the King of heaven, yet the King Himself declared them to be wrong. Understanding this is necessary for seeing how God’s answer to Job utilizes the opening chapters of Genesis, and in so doing, definitively reveals the identity of the Satan.

Above it was shown that Job’s prologue makes extensive use of Genesis 1-3, and it is the position of this study that the same is true of Job’s epilogue. This can primarily be seen by the fact that, just as Job 1-2 depicts the scene given to us in Genesis 1-3, so do the Lord’s speeches in Job 38-41 follow the exact sequence of events that took place in these same chapters. For instance, although it is not explicit, the text of Genesis 2:7-8 suggests that the Garden of Eden was planted before Adam’s very eyes, since Adam was created, then the Garden was created, and then Adam was placed in the Garden. This would mean that the very first thing Adam ever experienced was God’s creative power. After this, God brought the animals to Adam in order “to see what he would call them” (Gen 2:19). This is significant because in order to give the animals proper names, Adam first had to use wisdom to discern their nature,39 meaning that the second thing Adam ever experienced was learning wisdom from the animal kingdom. Finally, after naming all of God’s creatures, including his wife (Gen 2:23), Adam’s third ever experience was being confronted by the most cunning of all beasts, the infamous Serpent (Gen 3:1-7).

As mentioned, this exact sequence is paralleled in the speeches of God in Job 38-41. Like Adam, the first thing that Job experiences in his encounter with the Lord is His creative power. The Lord takes Job through every facet of creation, from “the foundation[s] of the earth” (38:4) to “the storehouses of the snow” (38:22) to the lioness and her cubs (38:39). After this, it comes as no surprise that Job is taught wisdom from God’s literary tour through the animal kingdom. Understanding that the Lord’s speeches are truly an answer to Job becomes particularly important here, because very often commentators will dismiss the Lord’s questions as impossible for someone like Job to answer. However, would it have been impossible for Job to know the time of year goats were born (39:2)? Did Job really not know who provides for the raven its prey (38:41)? Is it not more likely that, rather than merely “putting Job in his place,” the Lord was using this quasi-socratic dialogue as a teaching device? This was already alluded to in 12:7, “ask the beasts, and they will teach you; the birds of the heavens, and they will tell you,” not to mention that teaching via questioning is very characteristic of the God of Israel.40 As such, it seems that the Lord’s second speech to Job directly parallels Adam’s second encounter in the Garden, wherein he discerned wisdom from the animals.41

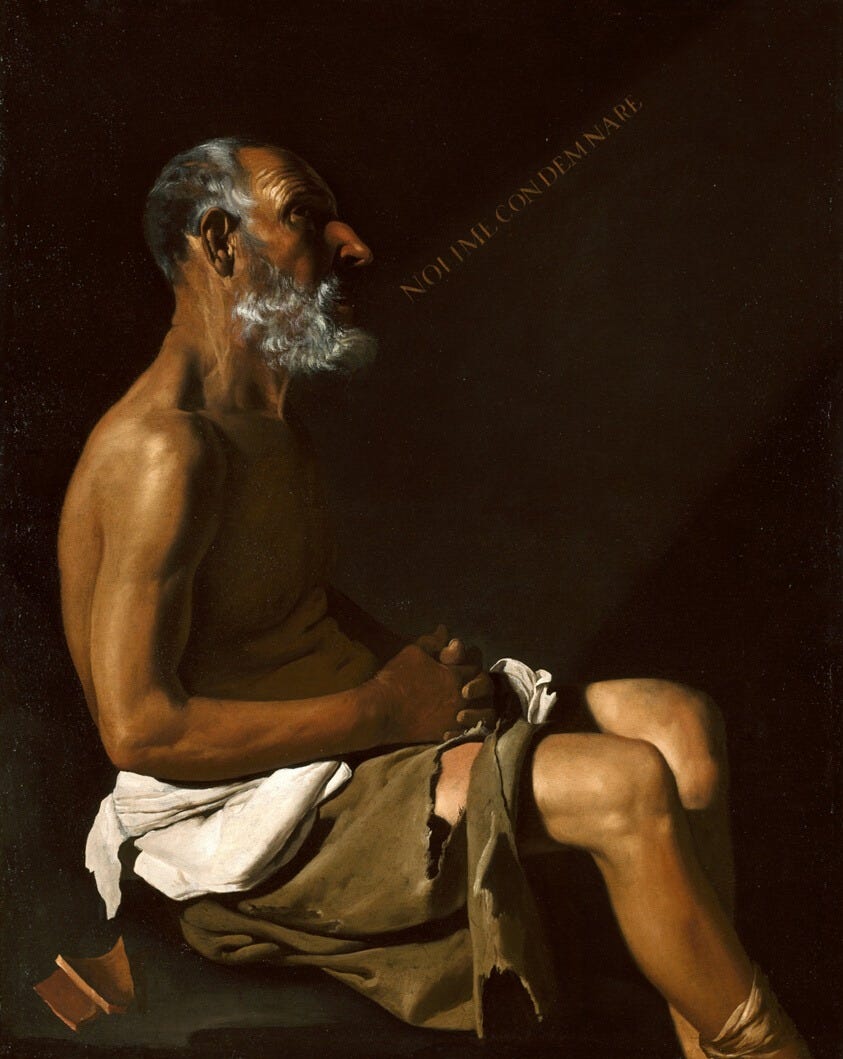

This is what sets the stage for God’s third and final speech, which we hold reveals the identity and purpose of the prologue’s Satan. Just as the third experience that Adam had in the Garden centered around his test by the Serpent, so does Job’s third and final lesson from God concern the nature of his test by the Satan. The Lord shows Job “Behemoth,” who is depicted as being “pierce[d]” through his nose (40:24), and then “Leviathan,” who is likewise “pierce[d]” with “a hook” (41:2) by which he is “draw[n] out” by the Lord (41:1). Importantly, Leviathan is directly identified as “the king of the sons of pride” (41:34), showing us that this is the prideful Satan from the prologue. Behemoth and Leviathan being led around by a hook in their nose conveys to Job the nature of his test. The Lord was the one who pointed out Job to the Satan (1:8, 2:3), He was the one who delivered Job into the Satan’s hand (1:12, 2:6), He has been providentially guiding the Satan’s work every step of the way, leading him around by his nose.42 But unlike Adam who failed his test at the hand of the Serpent, Job remained the Lord’s faithful servant even after being given over to the King of Pride, which is why he was vindicated in the end (42:7-8).

We can thus summarize our case for the Satan’s identity in Job’s epilogue in the following way: Just as Adam first experienced God’s creative power, and then learned wisdom from the animals, and then was put to the test by the Serpent, so too was Job first shown God’s creative power, followed by a lesson from the animal kingdom, after which he was finally shown the Leviathan-Serpent who had been behind his trials, his true adversary in heaven. This parallelism reveals that later Christian tradition was correct to identify the figure of the Satan with “that ancient Serpent” (Rev 20:2) who tempted the first parents of mankind.

Conclusion

The present study has been an attempted refutation of Peggy Day’s faulty analysis of the character of the Satan in the book of Job. It was first demonstrated that Day exhibits a false understanding of the way in which Job uses irony, since she believes that it could allow for the character of Job speaking falsely, while the actual text forbids this. Next, it was shown that Day undermines her own identification of 16:19’s “witness” with the Satan, and that it is much more natural to see the Lord Himself as both Job’s “witness” and “redeemer.” After tossing out Day’s theory, we then provided our own identification of the Satan by demonstrating that Job intentionally parallels this figure with the Serpent of Genesis 3, thus vindicating the traditional Christian interpretation of the heavenly adversary.

Day, Peggy L. An Adversary in Heaven: Satan in the Hebrew Bible, Brill Academic Pub, 1988, p. 71.

See Ibid., p. 71n6.

Seow, C.L. Job 1-21: Interpretation and Commentary, Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Publishing, 2013, p. 28.

Day, An Adversary in Heaven, p. 72.

Ingram, V. “The Book of Job as a satire with mention of verbal irony,” St Mark’s Review no. 239 (2017), p. 54.

Day, An Adversary in Heaven, pp. 90-101.

Ibid., pp. 84-85.

Ibid., p. 85.

Ibid.

Ibid., pp. 86-87.

Ibid., p. 94, emphasis mine.

Ibid., p. 89.

Ibid.

Ibid., p. 90.

Ibid., p. 92.

Ibid., p. 94.

Hartley, John E. The Book of Job, Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Publishing, 1988, p. 264.

Day, An Adversary in Heaven, p. 90.

Ibid., p. 91.

Leithart, Peter. “Triune Creator,” Theopolis Institute, 2021. Retrieved from https://theopolisinstitute.com/conversations/triune-creator.

Kou, Christopher D. “GOD’S STATUE IN THE COSMIC TEMPLE: צֶ֫לֶם and דְּמוּת in Genesis and the First Person Plural Cohortative of Gen 1:26 in Light of Sanctuary Setting and Christological Telos.” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 66.1 (2023), pp. 11-31.

Ibid., p. 28.

The Hebrew word used here, מָרוֹם, is also used in Job 25:2 and 31:2 to refer to the Lord being “on high,” lending further support to an identity between the Lord and the advocate.

Day, An Adversary in Heaven, p. 95.

Noah and Abraham are also referred to by a very similar term, תָּמִים (Gen 6:9, 17:1).

Passages like Genesis 3:24 suggest that Eden was a sanctuary akin to the Temple and Tabernacle, see Kang, Seung. “The Garden of Eden as an Israelite Sacred Place.” Theology Today, Vol. 77(1), 2020, pp. 89-99. Both the Temple and Tabernacle were tripartite structures, having a courtyard (Ex 27:9-19, 1 Kg 7:13–22), an inner sanctuary (Ex 28-31, 1 Kg 6:14-22), and holy of holies (Ex 26:31-33, 1 Kg 8:6-8). Likewise, Eden appears to have three parts: the tree of life, the tree of knowledge, and the fig leaves. Just as Israel’s later sanctuaries had these layers to keep the sacred protected from the profane, so it was with Eden’s garden.

In the former case, Korah, Dathan, and Abiram “gathered together against” Moses and Aaron, and in the latter case, Sanballat, Tobiah, and Geshem the Arab attempted to conspire against Nehemiah.

For a robust critique of the popular notion that the “duplicate” narratives of Genesis 1-2 serve as evidence for distinct sources, see Cassuto, Umberto. The Documentary Hypothesis and the Composition of the Pentateuch Eight Lectures. Varda Books, 2005, pp. 84-97.

Twenty two is a recognized numerical device in biblical poetry. See Labuschagne, Casper. Numerical Secrets of the Bible. Wipf and Stock, 2016, pp. 12-14.

This is almost certainly an allusion to “the tree of the knowledge of good and evil” from Genesis 2:9, see Davies, John A. “Discerning Between Good and Evil: Solomon as a New Adam in 1 Kings.” The Westminster Theological Journal, Vol. 73, 2011, pp. 39-57.

Solomon ended with a kingdom divided in two (1 Kg 11:31-35), Job ended with a kingdom multiplied by two (Job 42:10).

Day, An Adversary in Heaven, p. 95.

Sumpter, Toby J. Job Through New Eyes: A Son for Glory. Location 1703, Kindle edition, Athanasius Press, 2012.

Hartley, The Book of Job, p. 298.

Ibid., p. 299.

Seow, C.L. “Elihu’s Revelation.” Theology Today, 68(3), 2011, p. 264.

Sumpter, Job Through New Eyes, Location 2497, Kindle edition.

Ibid., Location 2546, Kindle edition.

The animals were “brought” (וַיָּבֵא֙) to Adam, and he discerned that they were not fit for him. After they had all been named, and still no helper was found, the woman was finally “brought” (וַיְבִאֶ֖הָ) to the man, and he declares that “at last” his search is over, “this is self of my self and flesh of my flesh.” Adam then names the woman just as he had named the animals: “she shall be called woman, because she was taken out of man” (Gen. 2:23). How did Adam know that the woman was taken from him since he was in a deep sleep while that happened (Gen. 2:21)? The answer is that Adam wisely discerned the nature of the woman, recognizing it as his own, and naming her accordingly. Thus, we can infer that this is something he likewise did for the animals.

This can be seen from Yahweh teaching Moses about His covenantal fidelity via questioning in Exodus 33:12-23, and Yahweh using a kind of socratic method to teach Abraham about His mercy and justice in Genesis 18:22-33. The Lord Jesus likewise instructs the rich young ruler about His divinity via questioning in Mark 10:18.

Recall that King Solomon, whom we have already tied to Adam and Job above, was most famous for his wisdom about animals (1 Kg 4:29-34).

This is further confirmed by parallel language in Ezekiel 29:3-4, “Behold, I am against you, Pharaoh king of Egypt, the great dragon that lies in the midst of his streams… I will put hooks in your jaws, and make the fish of your streams stick to your scales; and I will draw you up out of the midst of your streams.”

Beautiful work there, Mr Benjamin John,

Glad I found this article! Lots of clarity here!