In preparation for the upcoming Solemnity of St. Joseph, I’ve started doing a thirty three day Consecration to St. Joseph, which has inspired me to meditate on the importance of our great spiritual father among the Saints, “the patron of the universal Church.” One of my favorite ways to reflect on Saints, especially those present in Scripture, is by studying their relationship to other biblical Saints, types, and symbols. I’ve consistently found this method of studying God’s holy ones to be incredibly fruitful, and St. Joseph has proven to be no exception to this rule.

The New Joseph, the New Adam

Something Fr. Donald Calloway points out in his book is that there are many interesting connections between St. Joseph and the Old Testament patriarch, Joseph son of Jacob. Although it’s true that the patriarch Joseph is ultimately a type of our Lord Jesus—betrayed by his brothers (Judah in particular) for pieces of silver, thrown into the pit with two criminals, lifted up out of the pit, exalted to the right hand of Pharaoh at age thirty, fed the nations with bread—typology is layered.1 In 1 Corinthians 15:45, for example, St. Paul doesn’t simply call Jesus “the new Adam,” but rather “the last Adam,” implying that there were plenty of “new Adams” before our Lord. Along these lines, we can understand how St. Joseph is “the new Joseph.”

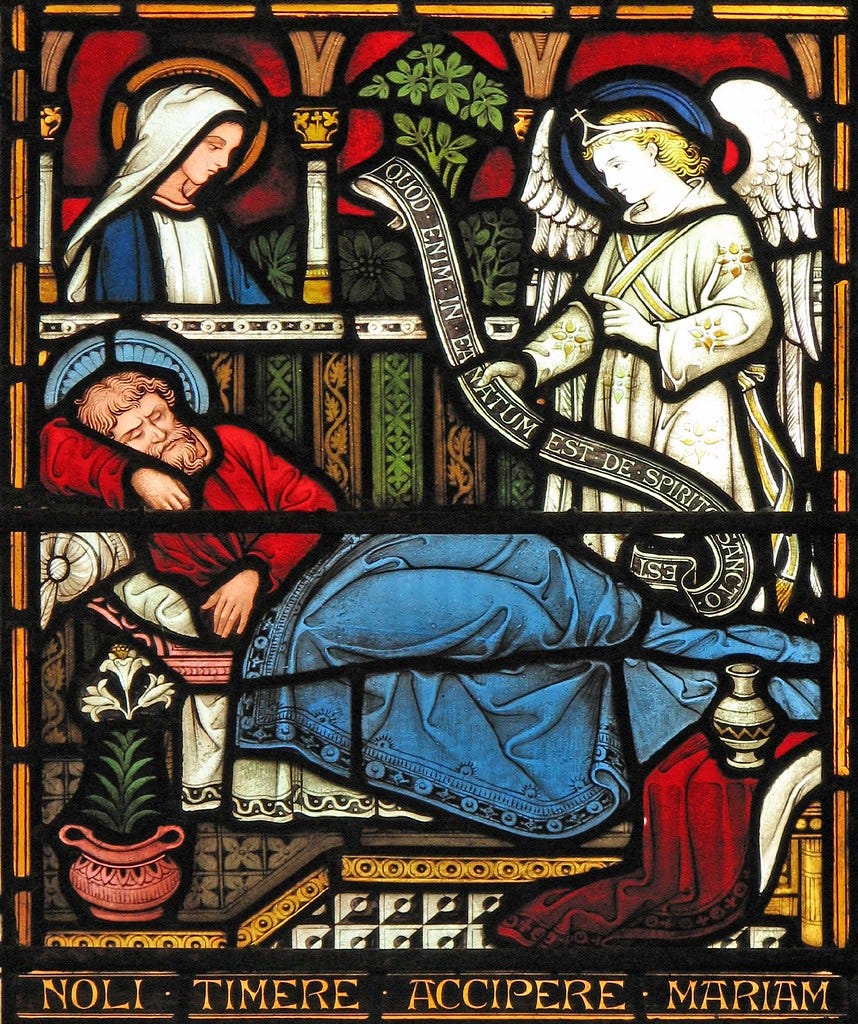

Like the patriarch Joseph, St. Joseph was the son of Jacob (Matt 1:16), and he received divinely inspired dreams about the land of Egypt (Matt 2:13). The dreams that the old Joseph interpreted were an injunction to store and protect the grain of Egypt so that it could be used to feed the nations during a time of famine (Gen 41:34-35). In a similar way, St. Joseph received a dream that he was to protect our Lord Jesus, the true Bread of Heaven, from Herod’s plan to slaughter the infants of Bethlehem, which he did by sheltering our Lord in the same land that Joseph stored up grain, Egypt. As many have noted, Bethlehem means “the house of bread,” and so by attacking the children of this city, Herod can be seen as the personal embodiment of the famine that swept over the land of Canaan, attempting to eliminate all of the “bread.” However, just as God raised up the patriarch Joseph to protect Egypt’s grain so the nations could feed on it and live, so too did He raise up St. Joseph to protect the Bread of Life so that the nations could eventually feed on Him and live forever. In this way, we have St. Joseph to thank every time we receive the Eucharistic Bread of Heaven.

St. Bernard of Clairvaux beautifully highlights this reality:

Keeping in mind the great patriarch Joseph, sold by his brothers in Egypt, understand that our saint has inherited not only his name, but even more, his power, his innocence, and his sanctity. As the patriarch Joseph stored the wheat not for himself, but for the people in their time of need, so Joseph has received a heavenly commission to watch over the living Bread not for himself alone, but for the entire world.

St. Bernard of Clairvaux, qtd. in St. Peter Julian Eymard, Month of St. Joseph, p. 7.

As does St. Lawrence of Brindisi:

Pharaoh, the mighty king of Egypt, exalted Joseph and made him the highest prince in his kingdom, because he stored up the grain and bread and saved the people of his entire kingdom. So Joseph saved and protected Christ, who is the living bread and gives eternal life to the world.

St. Lawrence of Brindisi, Opera Omnia: Feastday Sermons, p. 539.

Nor do the connections between the old and new Josephs end here. The patriarch Joseph is the climactic figure of Genesis because he is the new and redeemed Adam.2 Whereas Adam abused the knowledge of good and evil and saw his nakedness (Gen 3:4-7), Joseph was clothed in a royal coat (Gen 37:3), and could properly discern between good and evil after receiving dominion over the land: “You meant evil against me, but God meant it for good” (Gen 50:20). St. Joseph in the New Testament is likewise portrayed as a new Adam. Many are aware of the fact that the Blessed Virgin Mary is the new Eve,3 however, the implication of this is often ignored. If Mary is the new Eve, then St. Joseph, her husband, is the new Adam.

Recall that Adam’s chief duty in the garden was to protect his bride, a task he failed.4 This failure is reversed by St. Joseph who, as the husband and guardian of the new Eve, always protected his Bride. When Joseph found out that Mary was pregnant despite her vow of virginity, his instinctual reaction was to protect her from disgrace by secretly putting her away.5 After it was revealed to Joseph that Mary had conceived by the Holy Spirit, he immediately believed God, and his role as an Adam-guardian continued when he saved his Bride and Child from the serpent-king Herod. Rather than disobeying God and allowing his Bride to fall victim to the vicious attack of the serpent, St. Joseph exercised perfect obedience to the Lord’s command and saved her from this fate. In this way, Joseph foreshadowed the work of Christ, who Himself would go on to save His Bride the Church from the snares of the devil.

A Patron of God’s People

St. Joseph is thus the perfect mirror of his adopted Son, Jesus Christ. He is rightly called the “patron of the universal Church,” because if our Lord chose Joseph to protect His Sacred Body on earth, why would He take this duty away once Joseph acquired even more glory, strength, and power in heaven? If St. Joseph was called to protect the Blessed Virgin Mary herself, the immaculate symbol of our Lord’s Bride on earth, then why wouldn’t he be entrusted with protecting our Lord’s spotless Bride, the Church, from heaven? If these sound like baseless extrapolations, consider Revelation 20:4. This text shows us what “the millennium,” the age of the Church,6 looks like from a heavens-eye perspective. What we see is the Saints of God “reign[ing] with Christ” during this time, assisting our Lord Jesus in the government of His affairs on earth. One of the major themes of Revelation is that human beings will now be fulfilling the role of angels on the divine council.7 This is seen most prominently in Revelation 20:4 since, by sitting on thrones and reigning with Christ, the Saints are picking up the crowns that the angels “cast off” in Revelation 4:9-11.

Now, according to Jesus in Matthew 18:10, one of the tasks that angels have is to watch over the people of God, “the little ones” who constitute His Church.8 Acts 12:15 even shows a concrete example of the earliest Christians professing belief in “guardian angels.” So if, after the death, resurrection, and ascension of our Lord, human beings are now able to take up this same angelic task, the Catholic understanding of “patron Saints” follows quite organically.

Indeed, the way that both Matthew 18:10 and Acts 12:15 are worded implies that not every angel is assigned to the same person, but rather that each Christian has his own individual guardian angel. Daniel 12:1 further reveals that not only do individuals have guardian angels, but entire societies do as well, implying that God has assigned different angelic ministers to govern different parts of His creation (cf. Deut 32:8-9). Thus, once again, if the incorporation of human beings into the divine council is a defining feature of the new covenant, as the book of Revelation teaches, and one of the fundamental duties of angelic councilors is to act as patrons over various facets of the Lord’s kingdom, then it would absolutely follow that the universal Church has a patron Saint, perhaps even multiple. Although Daniel informs us that St. Michael was the “patron angel” of God’s people in the old covenant, Tobit 12:15 suggests that Michael was one of seven patrons, alongside Ss. Raphael and Gabriel (cf. Dan 8:16-17), and others who aren’t named. This means that the new covenant people of God, the Church, likely has multiple patrons as well, some of whom are easy to identify.

If any mere human beings are going to take the place of Israel’s patron angels, the Blessed Virgin Mary is obviously chief among them. Since time immemorial, the Christian faithful have revered our Lady as a unique patroness of the Church, and the Mother of all Christians (cf. Rev 12:17).9 She clearly takes over St. Michael’s role in the new covenant, acting as “the great Queen who has charge of God’s people.” However, as explained, there’s no reason why the Virgin Mary must be the Church’s only patron Saint. If old covenant Israel could have multiple “archangels” who watched over her, the new covenant Church certainly can as well.

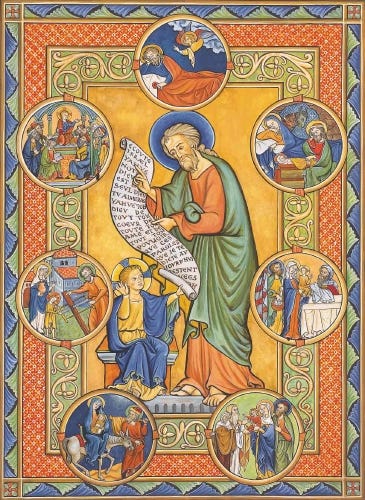

After the Virgin Mary, St. John the Baptist has traditionally been seen as the next great patron of the Holy Church. Unfortunately, as Peter Kwasniewski documents,10 modern Latin Catholic devotion to St. Joseph has largely replaced traditional Catholicism’s devotion to “the Holy Glorious Prophet, Forerunner and Baptist John,” an emphasis that has not been lost among our Eastern Catholic brethren. This reality is truly lamentable, as our Lord Himself called the Forerunner the greatest prophet who was ever born (Matt 11:11; Lk 7:28), the prophets themselves being the holiest category of men in Israel. John is the greatest among the traditionally greatest group of men. Unlike the other prophets who analogously pointed to Christ in their writings, the Baptist literally pointed to Him with his own hand!

This is why, in traditional Christian art and liturgy, St. John the Baptist is always seen next to the Virgin Mary, forever pointing the way to Jesus Christ, as he did while on earth. Even Latin Catholics today who only attend the Novus Ordo Mass will likely have picked up on this if they ever prayed the Litany of the Saints, “Holy Mary Mother of God, pray for us… St. John the Baptist, pray for us. St. Joseph, pray for us.” Those Catholics who regularly pray the Liturgy of the Hours might also have noticed that the two canticles that are prayed at Evening and Morning prayer surround the Virgin Mary (the Magnificat), and St. John the Forerunner (the Benedictus). This is why I strongly encourage my fellow Latin Catholics to rekindle their devotion to the Forerunner. There’s a reason Jesus spoke so highly of him, so let’s recognize this holy and glorious prophet and martyr (who died in defense of the sanctity of marriage, no less) as a unique patron of the Church! Let all Catholics actively seek the powerful intercession of the St. John the Forerunner, allow him to continuously point us towards the Lamb of God, and share with us his zeal for holiness and the truth.11

However, while the modern increase in devotion to St. Joseph has led to a decrease in the Church’s traditional devotion to St. John the Baptist, which ought to be corrected, this doesn’t mean that the more recent Catholic emphasis on Joseph is bad or should be thrown out. Indeed, the words of the Forerunner himself indicate that he’s not all that offended by the faithful looking away from him and towards someone else, “He must increase, but I must decrease” (Jn 3:30). Joseph’s name even means, “the Lord will increase.” While John is “the friend of the Bridegroom” (Jn 3:29), Joseph is the father of the Bridegroom (Lk 2:48), and he certainly deserves to speak at the wedding.

Recall the Litany of the Saints. In between the Virgin Mary, St. John the Baptist and St. Joseph, there’s an invocation of the three holy archangels, Ss. Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael. Today the Church even celebrates the feast of these three angels on the same day, September 29th. I would posit that the Virgin Mary, St. John the Baptist, and St. Joseph are the new covenant Saints that correspond to these patron angels that specially guarded the people of Israel in the old covenant.12 Mary is the new Michael, the great Queen who “keeps watch” over God’s people (cf. Dan 12:1; Rev 12:1-7). John is the new Gabriel, the herald of the Lord’s Advent (cf. Dan 8:16-17; Lk 1:19-33). Joseph is the new Raphael, the terror of demons (cf. Tob 12:3; 8:2-3 cf. Matt 2:13). Together, these three Saints constitute the greatest of the Church’s patrons, her guardians.

The New Raphael, Terror of Demons

Indeed, if we run with this apparent connection between St. Joseph and St. Raphael, it takes us in some very interesting directions. Consider that, in the book of Tobit, one of the primary ways that Raphael assists Tobias is by helping him obey his father’s instruction to take a wife from among his kinsmen (Tob 6:16). Raphael finds the perfect candidate—Sarah, the daughter of Raguel—but there’s a problem. Sarah “has been married to seven husbands,” and each one of them “died in the bridal chamber. On the night when they went in to her, they would die.” To make matters worse, it’s “a demon [who] kills them” (Tob 6:14). So Tobias is understandably hesitant to become husband number eight. However, St. Raphael insists that Tobias honor his father’s command, and teaches him how to drive away the demon and protect his future bride: “take some of the fish’s liver and heart and put them on the embers of the incense. An odor will be given off; the demon will smell it and flee… You will save [Sarah], and she will go with you” (Tob 6:17-18).

This turned out to be sound advice. On the night of their wedding, “Tobias remembered the words of Raphael,” and was able to drive out the demon Asmodeus and safely consummate his marriage with Sarah (Tob 8:2). This part of the narrative could end here, but the sacred text gives us a final detail that’s worth pondering: “The odor of the fish so repelled the demon that he fled to the remotest parts of Egypt. But Raphael followed him and at once bound him there hand and foot” (Tob 8:3). Raphael clearly wanted to ensure that Asmodeus never bothered Tobias and Sarah again, however, this does raise a question: why was Asmodeus so intent on killing all of Sarah’s husbands in the first place? Tobit 6:12 gives us a hint, “[Raguel] has no male heir and no daughter except Sarah only.” For some reason, the demon didn’t want Raguel’s bloodline to continue through Sarah. This should remind us of another Sarah whose seed the devil was intent on destroying—Sarah the wife of Abraham.13

Indeed, much of the Genesis narrative surrounding Abraham, Isaac, and Sarah can be seen as the unfolding of the “enmity” that exists between the woman and the serpent of Genesis 3:15. Satan and his demons know that the seed of the woman will eventually crush their heads, and so they’re hellbent on ending the bloodline of God’s elect. As Seraphim Hamilton documents, “In Genesis 12, the Serpentine Pharaoh attempts to seize the Woman… [but] Abram wisely deceives the Serpent, rendering a lex talionis back on the Serpent’s deception of Eve. [Then] in Genesis 20, the focus is on the second battle, between the Serpent and the Seed. The Serpentine Abimelech seizes Sarah to produce Seed through her, and this is Satan’s attempt to prevent the birth of Isaac.”14 This tension between women, seed, and serpents then continues in the book of Exodus, when the new Pharaoh “who did not know Joseph” arose (Ex 1:8), and attempted to destroy Jacob Israel’s bloodline yet again. But like Abraham and Sarah before them, the Hebrew midwives deceived the serpent and saved the promised seed who was to deliver Israel from the bondage of Egypt (Ex 1:17-20).

With this context in mind, it becomes clearer why the demon Asmodeus may have wanted to kill all of Sarah’s husbands—to stop the eventual birth of the promised seed. This is why St. Raphael had to chase Asmodeus into the land of Egypt and bind him there, to make sure he wouldn’t come back to threaten Tobias’ family. Circling back to the connection between St. Raphael and St. Joseph, perhaps you can see where I’m going with this. This is the exact pattern that plays out in St. Matthew’s account of the Holy Family’s flight to Egypt. The wicked king Herod has become a new Pharaoh, a new Asmodeus, attempting to destroy the promised seed. However, just as St. Raphael protected Tobias’ bride and their children by chasing Asmodeus into Egypt, so too did St. Joseph protect his Bride and Child by fleeing into the same land of Egypt.15 Like the wicked Pharaoh before him, Herod clearly “did not know Joseph” if he thought he could kill Jesus, “the son of Abraham” (Matt 1:1), “the son of Joseph” (Lk 3:23). St. Joseph is thus the new Archangel St. Raphael, the guardian of families, the terror of demons, and the patron of the universal Church.

Adoptive Father of the Son of God

Over the centuries, the Church has given St. Joseph many beautiful titles. “Mirror of patience,” “Pillar of families,” “Patron of the dying,” “Terror of demons,” “Patron of the universal Church,” among others. However, no title is so glorious as the one that God the Father Himself bestowed on our spiritual father: “Adoptive father of the Son of God.” To understand just how profound and awe-inspiring this title is, we ought to consider the sanctity of St. Joseph in light of the sanctity of his fellow guardians of the Holy Church, the Blessed Virgin Mary and St. John the Baptist.

Above it was noted that, unlike the other prophets who analogously pointed to Christ in their writings, the Forerunner literally pointed to Him with his own hand. It’s for this reason that our Lord considers St. John the greatest of the prophets “born of woman” (Lk 7:28). The prophets, many of whom were martyrs, were the greatest men in all of Israel on account of their closeness to God (see Deut 34:10; Amos 3:7), and since no prophet got closer to God than the Forerunner, he is the greatest among the traditionally greatest group of men. However, the Incarnation changed things quite a bit. Because our Lord came in the flesh, He created an entirely new category of “closeness to God” that previously did not exist. Some theologians call this the “hypostatic order,” and it explains why the Blessed Virgin Mary is greater than all of the prophets, even St. John the Baptist, despite not being a prophet herself.

The reason why our Lord granted Mary such extraordinary graces, making her more honorable than the Cherubim and more glorious beyond compare than the Seraphim, is because of her being uniquely predestined with Jesus Christ in the Incarnation. Whereas the prophets’ sanctity was rooted in their proximity to the Lord in their proclamation of Him, the Virgin Mary’s sanctity is rooted in her being inextricably bound up with what the prophets were proclaiming—the coming of the Lord in the flesh. This is where things get interesting when we turn to St. Joseph. Like his Immaculate Spouse, Joseph doesn’t stand in the line of prophets heralding the coming of the Lord, nor does he rank among the apostles or martyrs. However, everyone agrees that he at least surpasses the prophets, apostles, and martyrs in sanctity. Why is that? It’s because Joseph’s sanctity has the same origin and purpose as the Blessed Virgin’s—his unique relationship to the Incarnation.

Our Lord obviously didn’t take flesh from Joseph as He did from Mary. However, in the predestination of Christ, Joseph was essential—more essential than anyone after Mary, including more essential than St. John the Baptist. This is because the Father didn’t predestine His Son to be just any man, but rather to be Israel’s Christ, the son of David. In the economy of salvation, the Lord determined that royal inheritance only passes through the paternal line—a created image of the Father alone being the primordial fount of deity in the Blessed Trinity. As such, in the predestination of Jesus as the incarnate Messiah and King of Israel, St. Joseph’s role was, like the Virgin Mary’s, indispensable. Without Joseph consenting to be Jesus’ adopted father, our Lord would not “inherit the throne of his father David, and reign over the house of Jacob forever” (Lk 1:32). Without St. Joseph, Jesus is no Messiah at all, and the purpose of the Incarnation would be thwarted.

In this way, Joseph’s fatherhood reveals the profound reality of adoption, and sheds light on our own status as adopted sons of God. Seraphim Hamilton documents how the reality of adoption, and its connection to inheritance, is plastered all over the Old Testament: “Such adoptive logic is plain in Genesis 15, where Abram opens by saying that the heir of his household is going to be Eliezer of Damascus… In Levirate marriage, if a man’s brother dies without his wife bearing his children, the man takes the wife and she bears his children, but they inherit not their physical father’s land, but the father’s brothers land… Caleb [the spy] was a Kenizzite by birth [Num 32:11-12], yet Caleb had been adopted into the Tribe of Judah [Num 13:6 cf. Josh 15:12-13]… [and] receives inheritance in the land of Israel.”16 With this background, it makes sense why the Gospels trace Jesus’ royal lineage through St. Joseph (Matt 1:1-17; Lk 3:23-38), despite making it clear that our Lord was not his biological son (Matt 1:18-23; Lk 1:26-27, 34). Jesus is the ultimate image of how we can receive our eternal Father’s inheritance through adoption, and it was only possible because of Joseph’s fiat.

As St. Paul explains, because “the Spirit you received brought about your adoption to sonship,” we can, with Jesus, cry out, “Abba, Father!” (Rom 8:15). He writes further, “The Spirit himself testifies with our spirit that we are God’s children. Now if we are children, then we are heirs—heirs of God and co-heirs with Christ” (Rom 8:16-17). Whereas our Lord Jesus Christ is the eternal Son of God, the “natural” Son of the Father by virtue of receiving the eternal Spirit from Him, we are, by grace, the Father’s adopted sons through the reception of that same Spirit in baptism. This means that we, by adoption, have the same relation to the Father that the Son has by nature, and because of this, we receive His inheritance: the Holy Spirit.

St. Joseph’s title, “Adoptive father of the Son of God,” thus explains why he is the greatest Saint after Mary. Through the “Spirit of adoption,” we are “co-heirs with Christ” to the Father’s kingdom, and no greater image of this reality exists than our Lord receiving His own earthly inheritance through being the adopted son of St. Joseph. Joseph’s sanctity is, like Mary’s, derived from a unique category that is distinct from and superior to the category that the prophets (including the Forerunner) derive their sanctity from. In the words of the Dominican theologian, Fr. Reginald Garrigou Lagrange, “the reason why [St. Joseph] was predestined to the highest degree of glory after Mary, and in consequence to the highest degree of grace and of charity, is that he was called to be the worthy foster-father and protector of the Man-God.”17

The Glory of Saint Joseph

I’d like to end this article with a reflection on the manner in which Catholics honor great Saints such as St. Joseph. To most non-Catholics, it appears quite scandalous. While many of our Protestant friends can perhaps get on board with mentioning the Saints in our prayers, similar to how the Psalms include passing references to God’s angelic host (cf. Ps 103:20-23), they absolutely draw the line at praising the Saints by invoking their patronage. For example, they would likely condemn as idolatrous the beautiful prayer that Pope Leo XIII wrote to St. Joseph, “To you, O blessed Joseph, do we come in our afflictions, and having implored the help of your most holy Spouse, we confidently invoke your patronage also.” Now, while Protestants certainly are wrong to condemn these prayers as idolatrous, Catholics who attempt to defend our devotion to the Saints by saying that it’s no different from something like Psalm 103:20, “Bless the Lord, you His angels,” aren’t correct either. Instead, we have to recognize that the new covenant is truly new, because the exaltation of Jesus Christ to heaven fundamentally changed the way that human beings relate to the heavenly host.

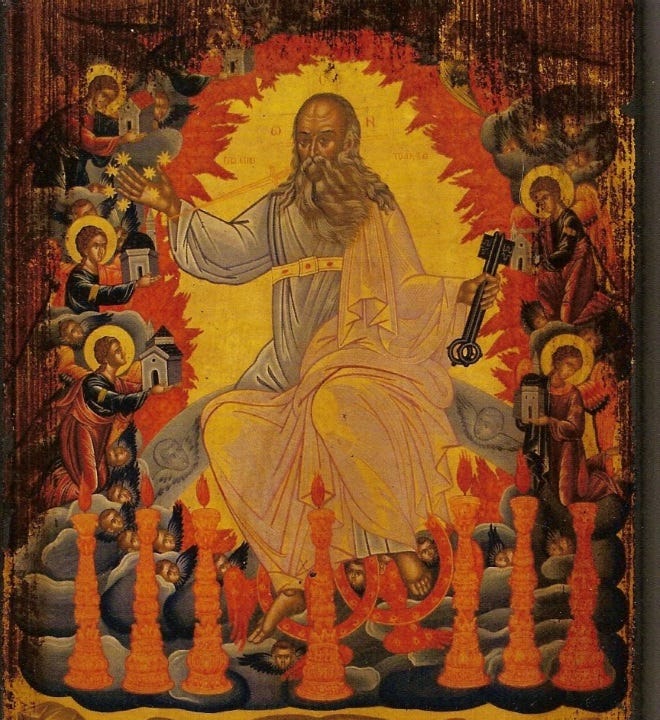

As noted above, this fact is brought out extensively in the book of Revelation, which itself builds on the prophecy of Daniel. In Daniel 7, the prophet “looks” and sees that “thrones were placed,” and he sees the “Ancient of Days” sitting on His throne in the midst of a divine courtroom (Dan 7:9-10). Then, the “Son of Man” approaches the heavenly throne and is “given dominion, and glory, and a kingdom, that all peoples, nations, and languages should serve him” (Dan 7:14). Already in Revelation 1, John identifies Jesus not only as the Son of Man, but also the Ancient of Days (Rev 1:12-15 cf. Dan 7:9, 13). This is why, when Jesus ascends to heaven and takes His “throne,” He’s surrounded by a council of twenty-four angelic “elders” (Rev. 4:1-11)—He’s back in the divine courtroom from Daniel’s vision. However, rather than sitting on their thrones with Christ, the angels cast off their crowns and “bow down,” προσκυνήσουσιν, before Him, because now it’s He who wears the crown (cf. Rev 6:2). The angels giving up their seats on the heavenly court tells us that humanity, starting with the man Christ Jesus, is going to replace them.

Returning to Daniel’s prophecy, consider the fact that Daniel identifies “the Son of Man” as “the Saints of the Most High.” When rephrasing Daniel 7:14, the prophet writes, “And the kingdom and the dominion and the greatness of the kingdoms under the whole heaven shall be given to the people of the Saints of the Most High; their kingdom shall be an everlasting kingdom, and all dominions shall serve and obey them” (Dan 7:27). It’s the Saints who are given “dominion, glory, and a kingdom,” it’s the Saints whom all peoples will “serve.” When commenting on Revelation’s usage of this text from Daniel, the Reformed theologian Peter Leithart writes, “[The] exaltation of the Son of Man in the exaltation of the saints is the theme of Revelation… The good news of Revelation is not merely the death and vindication of the Son; it is the death and vindication of the saints in him.”18 Jesus’ enthronement and veneration in heaven as the Son of Man, the Son of God, allows for the enthronement and veneration of His fellow sons of men, the adopted sons of God. This is what Jesus was constantly referring to when saying that He’s “going to prepare a place” for His followers by ascending into heaven (Jn 14:2-3). That “place” is a heavenly throne.

Thus, when we’re shown the divine courtroom again at the end of Revelation, John looks and “sees” the “thrones” from Daniel’s prophecy, and seated on them are the Saints whose souls have been exalted to heaven (Rev 20:4-6). It’s the Saints of the Most High who sit on their “thrones,” receive their “crowns” (cf. Rev 2:10, 3:11), and “reign with Christ” during the millennium. Through their glorification in the Spirit, the Saints have received “adoption to sonship” and truly become “heirs of God and co-heirs with Christ” (Rom 8:17). They have received the promise of 2 Timothy 2:12, “if we endure, we will also reign with Him.” Above it was pointed out how the Saints’ reigning with Christ entails the Catholic teaching that they have patronal dominion over the Lord’s kingdom, however, it goes further than this.

Recall how the angels of Revelation 4 “bowed down” before the enthroned Son of Man because He wore their crown. This suggests that, because mankind “was made for a little while lower than the angels,” before being “crowned with glory and honor” in the person of Christ (Ps 8:5 cf. Heb 2:7-8), the angels now bow down before the Saints who are enthroned with the Lord. Indeed, Jesus explicitly says that the Saints are to be venerated in Revelation 3:9, “I will make them [the Jews] come and bow down [προσκυνήσουσιν] before your feet, and they will learn that I have loved you.” This is an allusion not only to Daniel 7, which says that the nations will serve the Saints of the Most High, but also Isaiah 60:12-14, which describes Israel’s former enemies coming to “serve,” יַעַבְד֖וּךְ, and “bow down,” וְהִֽשְׁתַּחֲו֛וּ, before Zion and her citizens. As in Isaac’s prophecy that the nations would serve Jacob (Gen 27:28-29), these are the exact words used in the second commandment’s prohibition on idolatry. The message is clear: whereas you cannot serve and bow down before false gods, you are commanded to serve and bow down before the Saints, who are essentially “true gods” (cf. Ps 82; 86; 96).

This explains why Catholic devotion to the Saints is more lofty and exalted than old covenant Israel’s devotion to the angelic host. The new covenant is the unique age in which the nations serve and bow down to the sons of Jacob, an age that was foreshadowed in the story of the Old Testament patriarch Joseph. Right from the beginning we’re told that Joseph’s family is going to “bow down” to him, which indeed comes to pass (Gen 37:9-10; 42:6; 43:26-28; 47:31). This is because, unlike Adam, Joseph truly fulfilled his purpose as the image of God, and that’s why his being honored is such a major plot point in the Genesis narrative: true images are to be venerated. Hence in the present Messianic age, when those “predestined to be conformed to the image of [God’s] Son” are finally exalted to their rightful thrones in heaven (Rom 8:29), we absolutely must invoke, praise, and venerate them more than we would have in the days of old. And if this is true of all the Saints, how much more is it true of the second greatest of them, St. Joseph?

As St. Paul teaches, “There is one glory of the sun, and another glory of the moon, and another glory of the stars; for star differs from star in glory” (1 Cor 15:41). The Saints, who are “like the stars forever and ever” (Dan 12:3), have different degrees of glory, and the way we honor them should reflect that. In Paul’s analogy, the sun clearly refers to our Lord Jesus Christ, the Holy One of Israel, the Sun of Righteousness (Mal 4:2), who is owed not merely veneration and honor, but latria, the worship due to God alone on account of the hypostatic union. The moon refers to Mary, the new Rachel, who was mystically depicted as the moon in the patriarch Joseph’s dream (Gen 37:9-10), and is seen standing on the moon in St. John’s Revelation (Rev 12:1).19 As the most glorious of mere creatures on account of her unique relation to the hypostatic union, Mary is given hyperdulia, the most veneration we can licitly to pay to a mere creature. Then, “the stars” refer to all of the other Saints, the children of Abraham who are “like the stars of heaven” (Gen 15:5). As Paul writes, “star differs from star in glory,” and St. Joseph, because of his unique relation to Christ, is the one “predestined to the highest degree of glory after Mary.” It’s for this reason that he’s given protodulia, that is, the first and highest veneration we can give to a Saint after our Blessed Mother.

Therefore, let’s not be afraid to love St. Joseph! Especially during this month of March that’s dedicated to our Lord’s glorious adoptive father, let’s take refuge under his mantle, and allow him to lead us to his Son, Jesus Christ.

Concluding Prayer

O holy and righteous Joseph! While yet on earth thou didst have boldness before the Son of God Who was well pleased to call thee His father, in that thou wast the betrothed of His Mother, and to be obedient unto thee. We believe that as thou dwellest now in the heavenly mansions with the choirs of the righteous, thou art hearkened to in all that thou dost request of our God and Savior. Wherefore, fleeing to thy protection and defense, we beg and humbly entreat thee: as thou thyself wast delivered from a storm of doubting thoughts, so also deliver us who are tempest-tossed by the waves of confusion and passions; as thou didst shield the all-immaculate Virgin from the slanders of men, so shield us from all virulent calumny; as thou didst keep the incarnate Lord from all harm and affliction, so also with thy defense preserve His [Catholic] Church and all of us from all tribulation and harm. Thou knowest, O saint of God, that even the Son of God had bodily needs in the days of His incarnation, and thou didst attend unto them; wherefore, we beseech thee: tend thou to our temporal needs through thine intercession, granting us every good thing which is needful in this life. Especially do we entreat thee to intercede that we may receive remission of our sins from Him Who was called thy Son, the only-begotten Son of God, our Lord Jesus Christ, and that we may be worthy to inherit the kingdom of heaven, that, abiding with thee in the heavenly mansions, we may ever glorify the One God in three Persons—the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit—now and ever, and unto the ages of ages. Amen.

Prayer to the Holy and Righteous Joseph, The Betrothed of the All-holy Theotokos, qtd. in the Akathist Hymn To The Righteous Joseph.

For more on the connection between Joseph and Jesus, see my articles, “Joseph’s Resurrection,” and, “The Centrality of Joseph in Genesis.”

For more on this, see Seraphim Hamilton, “Joseph’s Harvest in the Messianic Vision of Genesis.”

For an exploration of Marian symbolism in Scripture, see my article, “The Hail Mary Prayer.”

As I explain in my article, “The Mariology of St. Paul,” “Paul writes that the reason he doesn’t permit women to have authority over men is because, “Adam was formed first, then Eve; Adam was not deceived, but the woman was deceived and became a transgressor” (1 Tim. 2:12-14). Contrary to popular sentiment, this is not so much a “put down” on Eve, but more so on Adam. Eve’s sin in the garden was due to deception, she just didn’t know any better, while Adam’s sin was not due to deception but rather deliberate choice. This is the difference between “sinning unintentionally” and “sinning with a high hand” (cf. Num. 15:27-31), Adam did the latter. The reason this entails men having authority over women is because, even though Adam failed his duty, it nonetheless reveals what that intended duty was: The man protects the woman, not the other way around.”

I understand that there’s a “pious belief” that the real reason St. Joseph tried to put Mary away was because he didn’t think himself worthy of being her and our Lord’s guardian, but this perspective is contradicted by Matthew 1:19. This text clearly identifies the reason why Joseph was going to put Mary away: “being a just man [he was] unwilling to put her to shame.” Why would Joseph being the adopted father of God’s Son have put Mary to shame more than consigning her to single motherhood? The obvious meaning of the text is that Joseph didn’t know how Mary got pregnant, and that’s why the angel had to clarify that she had conceived by the Holy Spirit, and not another man (Matt 1:20). Some argue that the Greek word δειγματίζω doesn’t mean “put her to shame,” but rather, “unveil her mystery,” but this translation isn’t correct. The only other time the New Testament uses this word is in Colossians 2:15, where it clearly has the connotation of “putting to open shame.” The 16th century Jesuit Francisco Suárez provides a more likely interpretation that is both honest with the text, and preserves the sanctity of St. Joseph: “Joseph was unable to judge or suspect the Virgin harshly. Influenced in one direction by the factual evidence he perceived, but swayed in the other by the exalted sanctity of the Virgin as he knew it from experience, he withheld all judgment because he was overwhelmed by a kind of stupefaction and great wonder. It was indeed a consummate act of justice not to be carried out of himself in so grave a matter, nor to be blinded by extreme passion or feeling. He persuaded himself that the event could have occured without sin. Consequently, he was unwilling to expose Mary; but since for him nothing in the matter was sufficiently clear, he believed that it pertained to justice to be separated from such a woman and to dismiss her in secret” (Suarez, In III, Q. 29, disp. 7, sec. 2, Nos. 5-6., qtd. in Francis Filas, Joseph: The Man Closest to Jesus, p. 143).

Indeed, consider how much more this interpretation redounds to the glory of our Blessed Mother. When Mary consented to be the Mother of God, she likely knew that she wasn’t to tell anyone—not even St. Joseph. God revealed it to her and St. Elizabeth, and so if He wanted Joseph to know, He would find a way to tell him. Unlike the other people who would encounter Jesus during His ministry, Mary didn’t need to be told to keep things a secret until the proper time. This shows Mary’s heroic faith. She knew that Joseph would wonder how she got pregnant, and yet she wouldn’t tell him unless God authorized it. She knew that, without an explanation, this would likely mean getting divorced—a terrible fate for women in the first century. But Mary wasn’t given any promises about what her ultimate fate would be, only that God was asking her to be the Mother of His Son, come what will. Nor does this detract from the holiness of St. Joseph in any way, since, if God chose to never reveal the origin of Mary’s Child to him, it would be irresponsible for him to not obey the Law and put away his wife. It would just be a situation where, in God’s Providence, no one was at sinful fault, both persevered in faithfulness to God, and yet they both had to endure hardship because of this.

As I explain in my article, “Ecclesial Infallibility in Scripture,” “Revelation 20:2-3 tells us that the millennium is the period in which Death and Hades are bound by the keys; and Matthew 16:18-19 tells us that the Church wields the power of these keys, and uses them to bind the gates of Hades. This therefore means that the millennium refers to the reign of the Church on earth, i.e. the present age.”

For more on this, see Seraphim Hamilton, “A Biblical Theology of the Invocation of Saints.”

For a defense of “the little ones” of Matthew 18 being Christians, see my article, “Binding and Loosing the Debt Prison: An Exegesis of the Parable of the Unforgiving Servant.” Also consider Nathan Eubank’s analysis of Matthew 18:10, “The heavens – the invisible realm of God‟s kingdom – is where God’s will is done. Jesus tells his followers to pray that God’s will be done on earth as well (6:10). For example, children have no status on earth, but Jesus warns his followers ‘See that you do not despise one of these little ones; for I tell you that in the heavens (ἐκ μὐνακμῖξ) their angels always behold the face of my Father who is in the heavens (ηὸ πνόζςπμκ ημῦ παηνόξ ιμο ημῦ ἐκ μὐνακμῖξ)’ (18:10). This fleshes out what it means to say that God’s will is done in heaven; on earth children are despised, but ‘in the heavens’ their angelic representatives behold the face of God. Jesus’ followers are to live according to the heavenly reality and become like a child ‘or you will never enter into the kingdom of the heavens’ (18:3).” (Nathan Eubank, Wages of Righteousness: The Economy of Heaven in the Gospel According to Matthew, 80-1).

See my article, “The Virgin Mary Against Protestantism.”

See Peter Kwasniewski, “Has Devotion to St. Joseph Supplanted Devotion to St. John the Baptist?.”

For specific devotions to the Forerunner, see Terri Thomas, “Prayers to Saint John the Baptist - An Overlooked but Powerful and Necessary Intercessor.”

It’s important to note that the Archangels have not been completely displaced by human beings, rather Jesus Himself says that angels still play an active role in the lives of Christians, as explained above.

For a detailed exploration of the book of Tobit’s usage of Genesis, especially the story of Abraham and Isaac, see Gary Anderson, Charity: The Place of the Poor in the Biblical Tradition, chapter seven.

Seraphim Hamilton, “Mary Through Biblical Eyes.”

Although the text doesn’t explicitly tell us, these connections lead me to believe that Raphael was the angel who appeared to Joseph in Matthew 1:20.

Seraphim Hamilton, “Jesus from Joseph?.”

Fr. Reginald Garrigou Lagrange, “The Predestination of St. Joseph and his Eminent Sanctity.”

Peter J. Leithart, Revelation, ed. Michael Allen and Scott R. Swain, vol. 1, p. 95.

For more on this, see my article, “Mary, Rachel, and the Moon.”

A real banger. Thank you, Ben!

I'm encouraged to see those of a younger generation using their knowledge of the eastern and western Catholic and patristic tradition to strengthen the Church.